Here in the Pacific Northwest, there are some who complain about the rainy weather and carry umbrellas to shield themselves from the elements. The rest of us call such people “pansies,” or perhaps “Californians.” As a native Portlander, I learned from a very early age to appreciate the beauty, the poetry, and the music in a pounding storm. The sound of rain and thunder was one of my very first lullabies.

This has led to what is perhaps my biggest problem with the story of Noah. Sure, there are other plot holes that have been pointed out ad nauseam: The structural insecurity of a wooden ship that size, Noah’s ability to build a ship that size with the tools and materials of the time, the ability of so many animal pairings to fit on an ark of the given proportions, the entire human race descended from Noah and his family, the wide variety of comparable ancient myths (Ziusudra being one example), the list goes on and on. But a solid month of non-stop pouring rain? That’s not an apocalyptic disaster, that’s February! Hell, if I wanted to see a city flooded in a torrential downpour, I could look out my window right now!

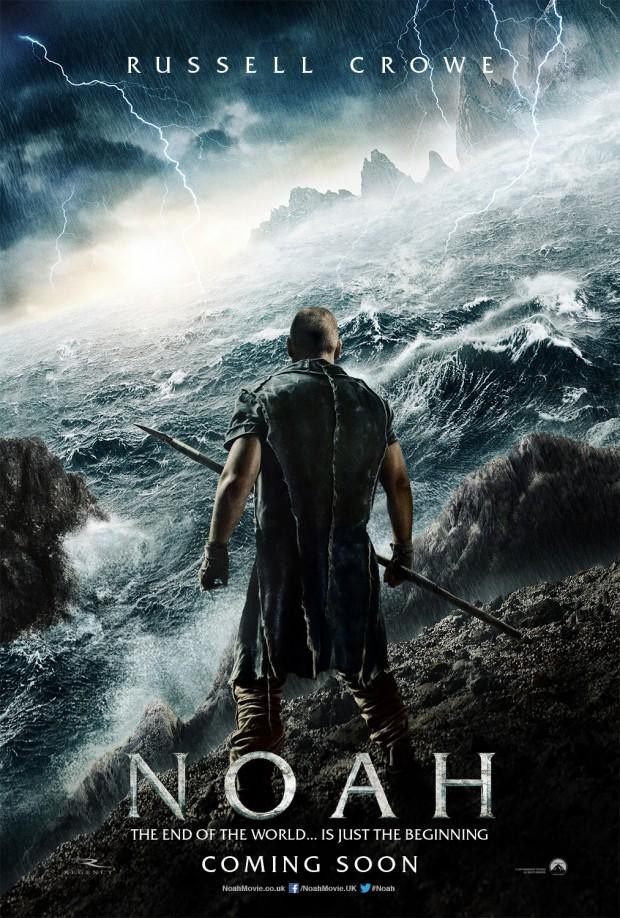

Yet here we are with Noah, which has apparently been a passion project to Darren Aronofsky for quite some time now. The film is already quite controversial, because of course some religious viewers take umbrage with the notion that Aronofsky adapted the Old Testament story with a few liberties. But then, as Aronofsky himself pointed out on a recent Colbert interview, the simple act of casting someone to play Noah is itself a creative liberty.

I’m not normally a fan of io9, but they posted a very interesting article about how Aronofsky’s adaptation fits in with different interpretations of the Noah fable. It seems that the Jews and Christians both have very differing viewpoints when it comes to Noah, but then again, Christians have been trying to reconcile the Old and New Testaments for the past 2,000 years or so. Basically, according to Annalee Newitz of io9, it seems that Aronofsky tended to side with the Rabbinical interpretations when he wasn’t subtly altering the story to comment on current events. This is understandable; taking the Jewish side when adapting the Jews’ book makes a lot of sense. Also, though Aronofsky self-identifies as an atheist, he was born and raised Jewish.

As I am a self-described agnostic who was born and raised Unitarian, I will defer to Newitz’ judgment in terms of the adaptation’s fidelity. Though I question the sanity of trusting io9 on anything this intellectual, it makes sense to me in this case. Regarding the adaptation’s quality as a film on its own merit… well, that’s complicated.

It seems pointless to recap such a universally-known story, but Aronofsky added a lot in here to seal up some plot holes and fill out the running time. I’m not entirely sure which additions were derived from existing theology — nor do I particularly care — so I’ll just fill in the blanks where the film does likewise.

The premise more or less begins after Adam and Eve got kicked out of Eden. They had three sons — Cain, Abel, and Seth — and of course Cain killed Abel. The two remaining sons went their separate ways, and Cain went east. He built a sprawling industrial empire that grew to cover the entire world. They destroyed the land and exhausted its natural resources, particularly zohar, an overt symbol for oil/coal/natural gas/pick-your-poison. All the while, the descendants of Seth were pushed further and further into what little wilderness remained.

(Side note: The word “zohar” is Hebrew for “splendor” or “radiance,” so Aronofsky isn’t pulling the word entirely out of thin air. Incidentally, “Zohar” is also the name of the book that serves as a foundation of the Judaism offshoot called Kabbalah.)

Right from the outset, the allegory should be obvious. The descendants of Cain were clearly made to comment on climate change, overpopulation, the concept of Manifest Destiny, and other concepts revolving around the general arrogance of man. Compare that to Noah, who represents a more environmental worldview, and his attitude of “build an ark for my family and everyone else can go fuck themselves” is quite reminiscent of modern-day survivalists. Of course, that doesn’t make him any more of a likeable character, but we’ll get back to that.

The film does address the matter of how one family could build such a massive ark, and the solution is quite clever. See, the film exposits that just after the whole Original Sin incident, there were some angels who took pity on Adam and Eve. So they were cast out of heaven and their fiery bodies blended with the earth below them. The so-called Watchers are now giants of rough igneous stone, very powerful yet slow and clumsy to move (except when the action scenes need them to be quick and lithe, anyway). The designs have a lot of character, and they move in a way that’s reminiscent of stop-motion. Very impressive.

Anyway, the Watchers have been feared by humanity for generations. But when they meet Noah and hear of his mission from God, they see a chance to finally atone for their defiance against the Creator. So Noah and his family get assistance from a dozen stone giants in the process of building and defending the ark. But wait, where will they get the materials in a barren wasteland? Well, it turns out that Methuselah (more on him later) has the last seed from the Garden of Eden. Noah plants it and a great forest springs up instantly. It seems pretty contrived to my agnostic reckoning, but what the hell, I’ll give the filmmakers the benefit of the doubt.

Then there’s the matter of God. Unlike some other Biblical epics, this one doesn’t feature an actor to play God, either in voice or in person. Instead, this portrayal of God speaks through visions and dreams. It leaves a measure of uncertainty that works for the story quite nicely, and of course Aronofsky uses a very special blend of psychedelic for his insane visions on film. The point being that God should be portrayed with an air of mystery, and that’s definitely how it’s done here.

That said, the film makes it clear that God is out there. The existence of God and the history of the world as detailed in Genesis are never doubted by any of the characters. Yet that brings a surprising new layer to the theological concepts of the film. It’s one thing to believe that God doesn’t exist and we’re screwed on our own. It’s another thing to believe that God exists and everything will work out to some crazy plan. But to know for an absolute fact that God exists and he’s left humanity to its own horrific devices for a dozen generations, only to destroy everything in a tidal wave anyway… well, shit. Of course the characters are going to be angry at their Creator.

It’s also worth noting that the film comes full stop at a point to briefly recap the creation of the universe. During this time, Aronofsky shows the Big Bang, the moon being formed by a giant rock hitting the planet, cellular division, evolution, and so on, taking a very metaphorical interpretation of Genesis. It doesn’t entirely work, given how notoriously hard it is to reconcile creationist “science” with our latest theories about the beginning of the cosmos. Still, the effort is appreciated.

The point being that in terms of scope, the film is perfectly fine. It has big ideas, it asks big questions, and the deities’ portrayal is suitably awe-inspiring. God’s wrath is on full display, and we can plainly see for ourselves that this is an Old Testament, less-loving-than-abusive father figure. It also helps that the CGI is passable (aside from a few dodgy moments), and a score from Clint Mansell is never a bad thing.

So what’s the problem? Well, it’s not an easy thing to pin down.

I think the big problem is that the film tries so hard to be a huge, profound Biblical epic and goes too far with it. I’m not saying that the film needed a ton of gratuitous humor, but a little strategically-placed comic relief can go a long way when you’re dealing with millions of men, women, and children getting slaughtered at the end of the world. The closest we get is Methuselah (Anthony Hopkins) asking for berries the way some old people would ask for candy. As you can probably tell already, it’s far too little to help.

By nature of the genre, the film paints in very broad strokes and tends to treat everything with profound importance. This naturally means a lot of overwrought moments, and this is especially true of the actors. None more so than Russell Crowe in the title role. I know this character is meant to be our protagonist, but it’s so hard to treat him as such for several reasons.

For one thing, Noah is a man who has the fate of the entire world resting on his shoulders. It’s hard relating to someone who bears that kind of a burden unless we see some hint of weakness under the strain, and Crowe’s performance showed none. I get the feeling that a different actor might have granted us a bit more emotion or charisma to latch onto, but with Crowe, his face is a solid mask of determined lunacy from start to finish. Through the entire running time (a couple of brief moments excluded), there’s never any hint of vulnerability or doubt, and his faith in the Lord remains unshaken. Noah is a man who receives his apocalyptic messages from God and he’s grimly determined to see his prophecies through to the end. No matter how bloodthirsty or completely insane the task may be, Noah shows no patience or compassion for anyone who gets in his way.

Which brings me to my next point: Noah is hopelessly misanthropic. See, he doesn’t think that his mission is to save ALL life — just the animals. Man, he reasons, is responsible for the evil that destroyed the world in the first place, and only animals are innocent because they’re the only ones still living as they did in the Garden of Eden. So as soon as their task is done, Noah’s family will be the last human beings left alive. Leaving aside the rank hypocrisy of stating that mankind is pure evil when this family is accomplishing such a monumental task for good, how on earth are we supposed to sympathize with a man who would kill his own children to ensure that all of humanity dies? Especially when we know in advance that humanity is going to keep on thriving no matter what he does?

Conversely, we have the antagonist. Tubal-cain (Ray Winstone) is a king who rules over his fellow sons of Cain. And he’s also the guy who killed Noah’s father, even though that serves no purpose to the plot. Whatever. The point being that Tubal-cain is there to represent the idea that mankind was made in God’s image and the world was made for us to conquer. Furthermore, Tubal-cain would argue that our own survival should come before the will of a deity who left this world to rot the way God did. Unfortunately, though Tubal-cain’s philosophy is understandable, it also means that he’s a completely selfish barbarian who would wipe out Noah’s entire menagerie just to keep himself fed.

On the other hand, at least Winstone had a measure of charisma that Crowe was sorely lacking. I can understand why armies would follow Tubal-cain to the gates of hell, but I have no idea why Noah’s family stuck by him for as long as they did. Frankly, if I had to choose between which of these two men would reshape the world swept clean, I think I’d rather kill them both and take my chances with the other characters.

Though keep in mind, that’s not saying much. Jennifer Connelly (here reuniting with her Requiem for a Dream director and her A Beautiful Mind costar) plays Noah’s wife, and she’s as bland a matriarch as I’ve ever seen. Douglas Booth (who previously starred in last year’s thrice-double-damned Romeo & Juliet adaptation) plays a horny and ridiculously handsome teenage boy, while Logan Lerman plays a horny and stupidly rebellious teenaged boy. Their adoptive sister is Ila (Emma Watson, who previously starred with Lerman in The Perks of Being a Wallflower), who’s stuck trying to juggle her feelings for the two boys while choosing which one to repopulate the world with. There’s also Leo McHugh Carroll, making his debut as Japheth the youngest son, but he’s not even worth mentioning. And I’ve already discussed Methuselah.

This is a whole family of thinly-developed characters, but I’d say Ila had the most potential wasted. Her character faces problems that are resolved far too easily, and the heavy responsibility of playing mother to an entire species is barely even addressed. Granted, that’s because the film is much more concerned with the family dynamic and the question of whether the human race is even worth continuing. If we only had characters who were easier to be around, those matters might be worth exploring.

To sum up, Noah put so much effort and ambition into the big things that it made some fatal errors in the small things. The philosophical matters, the effects, and Aronofsky’s interpretation of Judeo-Christian theology are all fascinating to watch, and the scale is appropriately gigantic. Unfortunately, the film put all of that before developing characters that we could go on this amazing journey with. When the most relatable character in your film is the hand-held camera, you know something’s gone terribly wrong.

I get the feeling that this was trying to be a great Biblical epic in the vein of Ben-Hur or The Ten Commandments, and there are times when it does come close to reaching those lofty goals. Except that Russell Crowe — bless his heart — is no Charlton Heston. I’d recommend a DVD viewing for those other three-hour epics, and that’s what I’m recommending for this one. Yes, I know that Noah is only two hours long, but it still felt way longer.