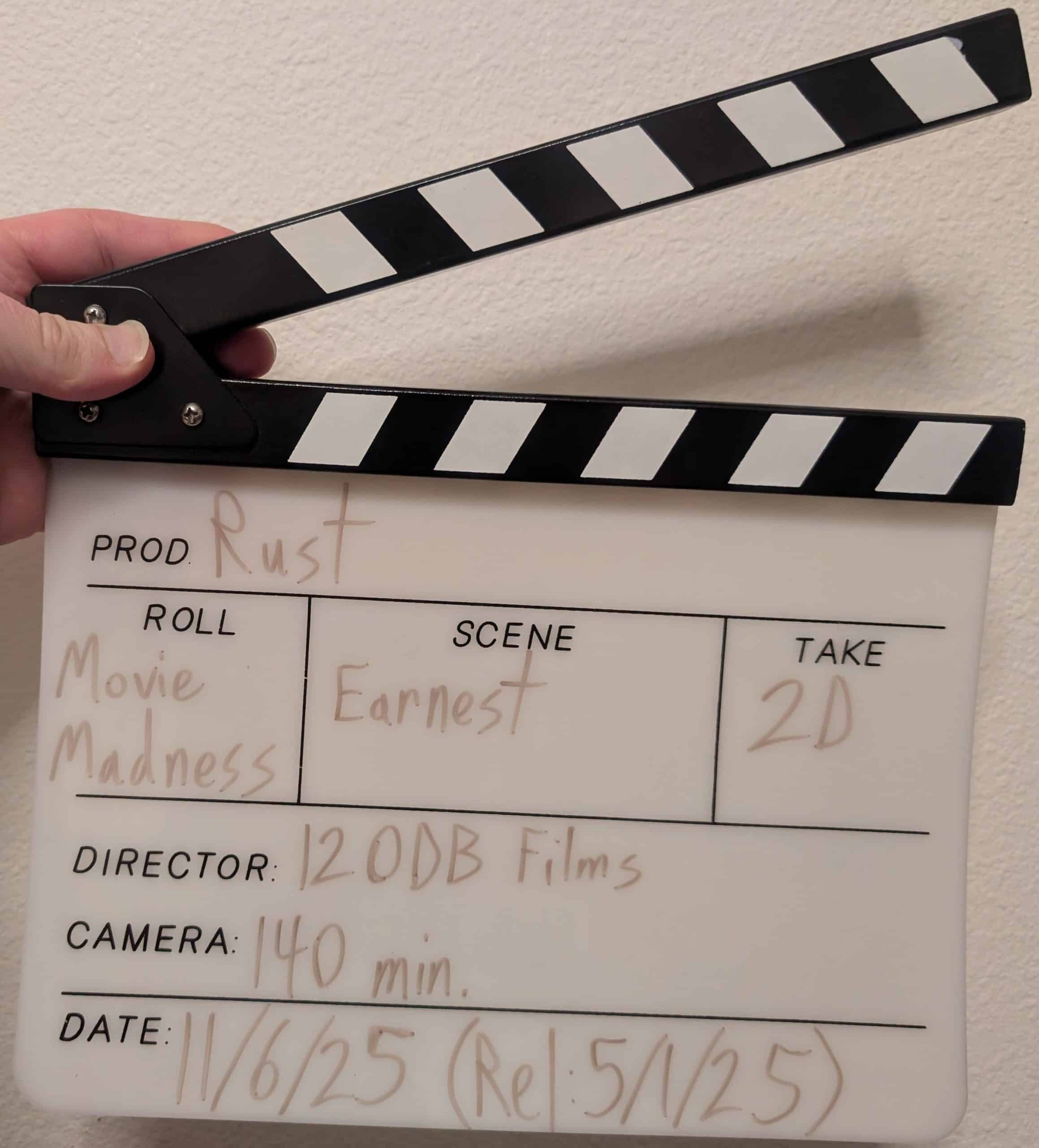

Yeah. We’re doing this, folks. Buckle up.

Rust comes to us from writer/director Joel Souza, who previously hadn’t made much of anything noteworthy. The only real headliner here is producer/story co-writer/star Alec Baldwin, who championed the script as a passion project of his. The film was given a paltry reported budget of $7 million, and cameras started rolling on October 6th, 2021. It was all downhill from there.

On October 21st — the twelfth day of filming! — a prop firearm discharged while Baldwin was rehearsing a scene. Cinematographer Halyna Hutchins was shot through the chest and killed. Souza was injured when the bullet exited her body.

Production was immediately halted. But not before pipe rigger Jason Miller had to be hospitalized, after he got bit by a brown recluse spider while closing the set. This fucking film shoot, man…

After all the lawsuits and controversies were settled, Baldwin was cleared of all manslaughter charges. Armorer Hannah Gutierrez-Reed plead guilty to negligence, got convicted on the involuntary manslaughter charge, and served 13 of 18 months. I might add that the judge publicly chastised the authorities for bungling the case and withholding evidence from the defense.

The shooting prompted the entire industry — including and especially this particular movie — to drastically overhaul best practices and make prop firearms safer. Production eventually resumed a year later, with Hutchins’ widower given a producer credit and Bianca Cline (late of Marcel the Shell with Shoes On) stepping in behind the camera. I might further add that two of the lead actors were no longer available, and so production more or less had to start from scratch.

I have neither the time, the inclination, nor the expertise to litigate the incident any further. I am neither qualified nor interested in speculating on who’s at fault or what (should have) happened. I’m only bringing this up at all because it would feel disrespectful if I didn’t.

What is the movie about? How good is it? In a sense, those questions are irrelevant. The bottom line is that someone died making it, and no film could possibly be worth that. Moreover, it could be argued that the box office grosses are effectively blood money, and any discussion of the film itself only distracts from the painfully real tragedy at the heart of it.

As such, I completely understand why nobody wanted anything to do with this film upon its release. There’s an argument to be made that the film never should’ve been finished at all, and I sincerely respect that perspective.

With all of that said, I can’t help but admire the tenacity of these filmmakers. With all this shit going on, through all the heartbreak and legal troubles, with a shoestring budget and literally the entire world rooting against them, the filmmakers got their movie finished and out the door. In any other context, that would be deeply admirable.

Weighing it all out, I can’t escape the conclusion that this movie needs to be chronicled. Nobody deserves to die making a movie, but I’m not sure that any movie deserves to be solely remembered for somebody’s death either. So I’m giving it the Movie Madness treatment, renting the DVD to be sure that I see it without giving any money directly to the filmmakers.

We lay our scene in Bumfuck, Wyoming, circa 1882. The film opens with Lucas Hollister and his little brother Jacob, respectively played by Patrick Scott McDermott and Easton Malcolm. Lucas is a 13-year-old boy, Jacob is maybe half that age, and the two of them are left alone to run the farm where their parents are buried. For obvious reasons, the both of them are nearly flat broke — aside from the farmland, a horse, and their great-granddaddy’s prized rifle, they’ve got basically nothing.

The plot kicks off when Lucas runs afoul of the town’s resident wealthy asshole (Charles Gantry, played by Gabriel Clark, representing Eugene!). Long story short, things escalate until Lucas accidentally kills Gantry. Lucas — a 13-year-old boy, remember — is summarily found guilty of premeditated murder and sentenced to hang.

(Side note: Yes, this is a movie about a main character who accidentally shoots someone to death, made to suffer through a public and blatantly unjust court trial for it. Not that anyone making the film could’ve known what happened behind the scenes, but I’ll let you finish that thought for me.)

Enter Harland Rust (Baldwin), a notorious shitkicker who just happens to be Lucas’ estranged grandfather. Rust breaks the boy out of jail with the goal of getting him down to safety in Mexico. This great idea is naturally complicated by the $1,000 bounty on their heads and everyone in the American Southwest looking to collect it. And so we’re off to the races.

The film spends a lot of time — probably too much, honestly — focused on the lawmen and bounty hunters chasing after Rust and Lucas. Too many are featureless filler for the victim pool, and some are insufferable comic relief who actively do more harm than good. (The worst cases in point are the squabbling brain-dead Lafontaine Brothers, played by Rhys Coiro and Devon Workheiser.) But there are two in particular worth pointing out.

On one hand is Elwood “Wood” Helm, played by Josh Hopkins. He’s a burned-out U.S. Marshal, grappling with his long history of violence on the job while he and his wife are also caring for a fatally diseased son. On the other hand is Fenton “Preacher” Lang, who comes from a long line of bounty hunters. I should perhaps point out that Helm has a badge and he’s dressed all in white, while Lang has the fancy facial scars and he’s dressed all in black.

What’s interesting is that Helm is deeply troubled by how little times change, even after all the men he’s captured and sent off to the gallows. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that he’s dwelling on these thoughts while his son is suffering a slow, painful, dreadfully premature death. The end result is that Helm doesn’t believe in his job anymore and he’s become thoroughly convinced that God doesn’t exist, but his conscience compels him to keep moving forward just in case he turns out to be wrong.

By contrast, “Preacher” Lang professes to be a devout Christian, and he’s more than happy to talk about his faith at great length to anyone who will listen. Even as he’s shacking up with a prostitute, seducing a woman into giving up vital information, killing and capturing people for money, etc. So we’ve got a sociopath who’s a devout Christian, acting opposite a man who’s got a strong sense of morality and justice that God doesn’t enter into. It’s a film that’s anti-religious, almost to the point of nihilistic, but it certainly makes for thought-provoking drama.

That said, of course the real focal point here is the Rust/Lucas interplay. It’s got issues. To start with, Rust is clearly supposed to be the kind of grizzled stone-cold badass that might be played by someone like Stephen Lang or Josh Brolin. For all his strengths as an actor, Baldwin isn’t in that same class. He’s putting in his best effort, which certainly isn’t awful, but the script is reaching much farther than his grasp will allow.

Lucas has the opposite problem. There’s no doubt in my mind that McDermott was capable of anchoring this movie and matching Baldwin’s intensity, but the script keeps holding him back. The big problem here is that Lucas is supposed to be a kind and soft-hearted kid in a time and place that actively punishes people for being too soft and compassionate. Lucas’ whole deal is that he’s in over his head, running for his life through circumstances that he’s neither physically nor mentally equipped for.

In other words, we’ve got a protagonist who’s demonstrably incapable of dealing with the movie around him, yet he’s supposed to remain sympathetic and compelling all throughout the movie around him. More experienced and talented filmmakers than Souza have tried and failed at striking that balance.

Lucas is a protagonist with basically zero agency, which is always a fatal error. He barely ever contributes to the plot unless he’s making some mistake or getting into some trouble that Rust has to save him from. Yes, it’s totally understandable that a 13-year-old boy could not reasonably be expected to deal with this situation. Yes, I understand how such a young boy would be upset and even a little bit whiny about running away from home and toward an uncertain future because of some accident that wasn’t even really his fault. Even so, there comes a point when we expect to see our protagonist grow and develop. I can only watch so many scenes of Rust calling his grandson a hapless dumbass before it gets old.

To be entirely fair, Lucas got into this whole mess precisely because he raised a gun to defend himself. As such, it might be understandable why he’d be hesitant to use violence again. Trouble is, the film never goes there. The closest we get is Lucas’ observation that literally anyone who picks up his great-granddaddy’s rifle ends up getting destroyed by it.

In theory, I like the idea of a particular rifle used as a symbol of violence. In practice, the rifle tends to cause fatal misfortune in highly specific and peculiar ways. While I’m sure the intended message was something to the effect of “violence always cuts both ways”, the conveyed message is more to the effect of “this particular gun is goddamn cursed.”

With all of that said, the film is undeniably gorgeous. Every frame is a work of art, from start to finish. It’s abundantly clear that this was made and completed in tribute to a great cinematographer gone far too soon. I might also add that for all my complaints about the bloated plot, the various storylines all dovetail together beautifully for a climax that’s great fun to watch.

The bottom line here is that in so many ways, Rust flew too close to the sun. This was a highly ambitious movie that set out to be a western epic drama about crime and punishment, good and evil, sin and redemption, violence and compassion. Unfortunately, while the broad strokes are all marvelous, it suffers in the fine details. I don’t know that a larger budget would’ve helped, but a cast of stronger actors certainly wouldn’t have hurt.

Everything about this movie comes down to an auteur punching above his weight class as a writer/director and an actor punching above his weight as a producer. If Souza had given the script another polish and handed it off to a more experienced director, things likely would’ve turned out much differently. As it is, the behind-the-scenes drama and tragedy turned out to be the most interesting thing about this movie, and that’s a damn shame.